9 Pinoy Historical “Bad Guys” Who Weren’t As Bad As You Think

We know them as the quintessential bad guys of our history. However, as the saying goes, there’s more than meets the eye.

As we’ll find out later on, centuries of non-stop propaganda, vilification, etc., tend to leave a nasty mark on people’s memories, rendering them unable to see these (in)famous personalities in a positive light or at the very least in a more forgiving manner.

While not totally blameless, these historical villains also deserve a break from the undeserved relentless bashing we’ve subjected them to.

Also Read: 7 Reasons Why Filipinos Hate Emilio Aguinaldo

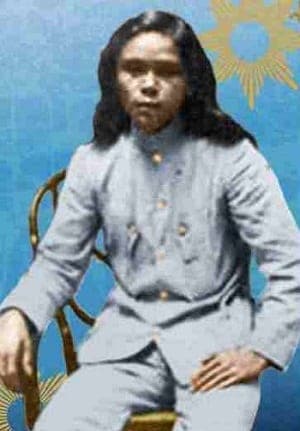

1. Macario Sakay.

Decades of being vilified by the Americans has made Macario Sakay a mere bandit in the minds of many Filipinos. Fortunately, however, contemporary historians now say Sakay—the long-haired founder of the Tagalog Republic who continued resisting American rule long after the surrender of many revolutionaries—was actually an ardent patriot and nationalist.

Also Read: Macario Sakay’s famous last words

Far from being the leader of a group of brigands, Sakay held sway over a functioning government complete with a regular armed force in several areas under his rule. If anything, it was actually the Americans who deserved to be criticized for backstabbing Sakay when in 1906 they falsely promised him amnesty in exchange for him surrendering. Instead of keeping their promise, they instead arrested Sakay and sentenced him to be hanged on charges of brigandage.

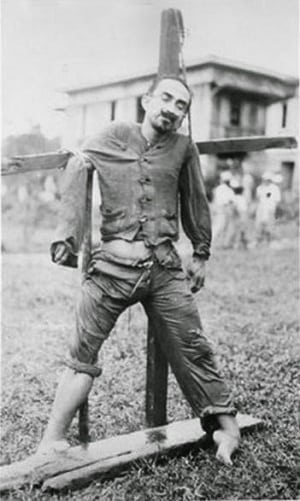

2. Teodoro Asedillo.

Known as the “Terror of the Sierra,” Asedillo was characterized by the Americans as a bandit who terrorized the countryside with his group of lawless elements. However, just like Sakay, Asedillo’s acts—so long vilified as banditry—actually reflected his nationalism.

A school teacher, Asedillo continued teaching his students the Filipino language and culture at a time when the Americans explicitly banned them from the classroom. After being removed from his position, Asedillo found work as the chief of police in his hometown of Longos, Laguna.

When he was yet again left jobless with the election of a new administration, Asedillo found work in the hinterlands as a farmer and founded the labor movement Katipunan ng mga Anak Pawis in 1929 to protest the unfair labor policies of the government.

READ: 9 Extremely Notorious Pinoy Gangsters

After being implicated in a factory strike in Manila which killed two policemen, he later went into hiding in the Laguna-Tayabas areas where he was hailed as a folk hero for stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. Government forces finally tracked and killed him in his hideout in 1935, after which his body was displayed and paraded in the public plaza by the authorities.

3. Artemio Ricarte.

We know him mainly as one of Andres Bonifacio’s generals and the co-founder of the pro-Japanese group MAKAPILI. Now you might be wondering why on earth would a revolutionary general establish a group bent on aiding the Japanese who clearly were oppressing his fellow countrymen.

For starters, Ricarte was clearly a nationalist. Unlike many of his fellow generals, Ricarte refused to take an oath of allegiance (several times in fact) to the Americans and was deported to Hong Kong for his refusal. To escape further scrutiny, he and his wife later went and settled in Japan. When World War II broke out, the Japanese flew him back to the Philippines and exploited his nationalism for their own evil designs.

Related Article: 11 Reasons Why Jose P. Laurel Was A Total Badass

In essence, Ricarte’s desire to see his country free from foreign domination ended being used against him. To his credit, he was never pro-Japanese but pro-Filipino, as exemplified when he spurned Japanese offers to fly him back to the relative safety of Japan because he had to be with his people in their time of distress. In the end, he died of dysentery in Hungduan, Ifugao, a patriot up to his last breath.

4. Benigno Ramos.

Aside from being a co-founder of the MAKAPILI, Ramos was also the leader of the pro-Japanese political party “Ganap” and earlier, the peasant Sakdalista Movement which advocated radical land reform and complete independence from the US.

While he may have undoubtedly looked like a whining militant/pro-Japanese collaborator, a closer look at Ramos’ life would reveal he was a nationalist at heart. Originally a teacher at a high school in Manila, he had joined an unauthorized strike after an American teacher derided the students with racial slurs. After resigning from his post, he created his newspaper Sakdal (“to accuse”) wherein he outlined the grievances of the masses against the government and the Americans whom he accused of enriching themselves at the expense of the lower classes.

Also Read: 10 Biggest Misconceptions About World War II In The Philippines

Ramos’ followers later staged a failed uprising on May 2, 1935, forcing him to seek exile in Japan. As with Ricarte, the Japanese exploited Ramos’ desire for an independent Philippines, bringing him back to his country and using him for their own ends.

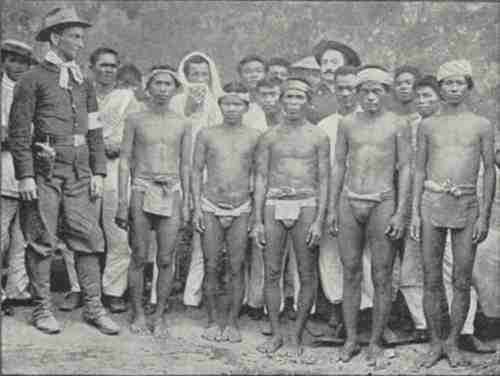

5. The Macabebes.

Certainly, no other group (except probably for the Moros) has been vilified so much as the Macabebes of Pampanga, to the point that the mere mention of their name brings up the “dugong-aso” tag.

In their defense, however, the Macabebes (and the Kapampangans by extension) have had a long history of fighting foreigners. In fact, it was a Macabebe, Tarik Soliman, who alone refused to bow to Spain unlike his fellow chieftains Matanda and Lakandula, fighting and perishing in the 1571 Battle of Bangkusay.

In the said battle, Tarik had to fight Miguel Lopez de Legaspi’s Tagalog allies as well, an incident which may have started the rift between the two groups. Over the centuries, Spain made use of the Macabebes’ fighting prowess, employing them as professional soldiers against Chinese pirate Limahong, the Dutch, and the British.

When the Philippine Revolution broke out, only the Macabebes stayed loyal to Spain even as their fellow Kapampangans pledged their allegiance to Emilio Aguinaldo’s man General Maximino Hizon. In retaliation, Antonio Luna had the town of Macabebe razed to the ground. This incident would spur the Macabebes to fight under America’s banner, a decision which culminated in the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo.

Also Read: 8 Extremely Interesting Lesser-Known Battles in Philippine History

6. The Aswang.

Ok, so you may be wondering how the (fictional) Filipino embodiment of evil incarnate could possibly get any less evil and scary. Well, if there’s anyone to blame for making the aswang the enduring bogeyman used to scare mischievous Filipino children into behaving, it would have to be the Spanish.

Capitalizing on the superstitious beliefs of our ancestors, the Spanish made good use of the aswang myth to command obedience and stifle any dissent from the natives. In time, indigenous practices and customs (especially those related to the women babaylan) became equated with the aswang. It has even been suggested that the Spanish slowly molded the native aswang into a fetus-eating bloodsucker to vilify the once-nurturing role of the babaylan as the midwife and healer of her community.

Also Read: Top 10 Lesser-Known Mythical Creatures in Philippine Folklore

Regardless, they managed to dismantle the social hierarchy of the natives, relegating the once-highly regarded women to the confines of their homes in consonance with the Maria Clara archetype. Apparently, even with the going of the Spanish, belief in the aswang has continued to pervade modern society.

7. Januario Galut.

History has not been kind to Januario Galut, the man known by many as the one who supposedly betrayed Gregorio del Pilar at the Battle of Tirad Pass, leading to the former’s death at the hands of the Americans. However, was Galut really a low-life traitor as history has made him out to be?

Recommended Article: 8 Dark Chapters of Filipino-American History We Rarely Talk About

Unfortunately for a polarizing figure such as Galut, little is known about his actual life and the circumstances that may have led him to side with the Americans. However, as what can be inferred during his time, his tribe may have been compelled to switch sides after the thorough discrimination an all-Igorot contingent suffered at the hands of the revolutionaries when they were forcibly recruited to fight the Americans in Caloocan.

Along their journey from the Cordilleras to Manila, the Igorots were discriminated by the residents and were also deprived of proper rations and rest by the revolutionaries. Aside from that, they were also threatened with execution should they desert.

Nevertheless, the 200 Igorot warriors—armed only with spears and axes—surrendered to the Americans after the Battle of Caloocan and later on became their guides in the mountains—an act which could be interpreted as payback for the ill-treatment they received from their fellow Filipinos.

8. Lazaro Makapagal.

Aside from being the ancestor of two past Philippine presidents, Makapagal is also known for the dubious distinction of being the chief executioner of Andres Bonifacio and his brother Procopio.

Also Read: 7 Fascinating Facts You Didn’t Know About Andres Bonifacio

While we won’t delve anymore on the methods used to kill the Bonifacio brothers nor speculate on who was the real mastermind behind their execution, we would point out that Makapagal most likely had no hand in the conspiracy, much less know he was going to kill the Supremo. Proof of this lies in the existence of the sealed letter which every source mentions. Makapagal received this letter from General Mariano Noriel (the leader of the Council of War who tried the Bonifacio brothers) who instructed him to open it only after leading Andres and Procopio to Mt. Maragandon.

In all likelihood, Makapagal didn’t have an inkling he would be serving as the Bonifacio brothers’ head hatchet man. He may also have performed the execution under duress because the letter clearly stated if he didn’t carry out the order, he and his men would face a severe court-martial.

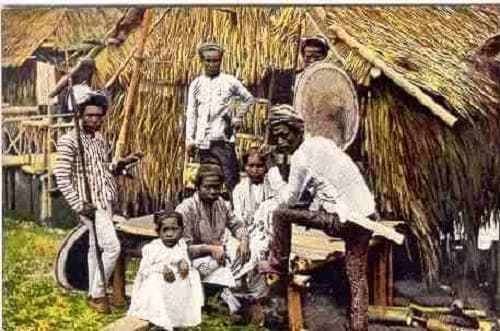

9. The Moro People.

Like we’ve said, it’s probably the Moro people who have been given a far-bigger historical bum rap than the Macabebes. Although we may not care to admit it, centuries of vilification by the Spanish and decades of discrimination by the Americans have given us a rather dim view of the Moro people, leading us to forget that they are the proud owners of a rich culture and history in the Philippines spanning more than 500 years.

Also Read: Meet the Terrifying Moro Warriors and Heroes of WWII

For the Spanish, their ardent desire to Christianize the entire country led them to revile Moros as unholy heathens. This, of course, was spread among the Christianized natives by way of propaganda, the most famous example being the “moro-moro.”

As for the Americans, they extended their “Manifest Destiny” to include the Moros which resulted in systematic land-grabbing of Moro-held territory and the resettlement of the Moro people, the after-effects of which can still be felt today with the internecine conflict and economic depression prevailing in Mindanao.

References

Alim, G. (1995). In European Solidarity Conference on the Philippines – Philippine Solidarity 2000: In Search of New Perspective. Hoisdorf, Germany. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/LcoZue

Cristobal, A. (1997). The Tragedy of the Revolution. Makati: Studio 5 Publishing.

De Leon, J. (2012). IJuander: Why do Filipinos still believe in aswang?. GMA News Online. Retrieved 9 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/pHGzkQ

Dumindin, A. (2006). Capture of Aguinaldo, March 23, 1901. Philippine-American War, 1899-1902. Retrieved 9 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/3UZDWh

GMA News Online,. (2011). Guro na humawak ng armas para sa kalayaan ng mga Pilipino. Retrieved 9 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/BpCb9i

Guerrero-Nakpil, C. (2008). The mark of Sakay: The vilified hero of our war with America.philSTAR.com. Retrieved 9 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/hU3ki1

Jose, R. (1999). Exile as Protest: Artemio Ricarte. Asian And Pacific Migration Journal, 8(1-2), 131-156.

Ocampo, A. (2013). An Igorot in the Philippine-American War. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 9 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/CT5F8P

Orejas, T. (2014). Macabebe Stigma: The fight to remove ‘dugong aso’ tag. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 9 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/qS17dM

The Kahimyang Project,. (2012). Today in Philippine History, October 13, 1930, Benigno Ramos released a printed newspaper, called Sakdal. Retrieved 9 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/IJ4Y3v

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net