The First Warrior-Hero Who Died Fighting For Our Freedom

When the Spanish explorer Miguel López de Legazpi arrived in Manila in 1571, he knew what he wanted–and he wanted it fast.

A year earlier, while he’s still in Panay, he ordered Martin de Goiti to explore the northern region accompanied by Spanish soldiers and some of their Visayan allies. The expedition proved to be a success: Goiti and his men came back with the news of their victory over the Tagalog warriors led by Rajah Soliman (or Sulayman).

Also Read: 8 Extremely Interesting Lesser-Known Battles in Philippine History

Legazpi saw an opportunity. Finding the stories of the ancient kingdom of Manila being a rich trading center too irresistible, he set off north. And unlike in Goiti’s voyage, a stronger army was now rallying behind Legazpi’s back–a total of 27 vessels, 280 Spaniards, and over 600 Visayan warriors.

You can just imagine how the Tagalog tribal leaders felt when this overwhelming sight started appearing on the horizon. Clearly outnumbered, Lakan Dula of Tondo had no choice but to concede and convince his brother and nephew–Rajah Matanda and Rajah Soliman, respectively–to do the same.

In the end, the Europeans were welcomed with open arms. Legazpi, in response to their hospitality, assured his newfound allies that he arrived “to teach them the true law of the one, all-powerful God, creator of heaven and earth.”

If only they knew better.

As soon as the alliance was made, Legazpi took hold of the ancient kingdom of Manila in the name of King Philip II of Spain. He even demanded the natives to build a big house for him, a chapel for the Bible-wielding friars, as well as 150 medium-sized houses for the Spanish soldiers.

But little did Legazpi know, the war was far from over yet.

Also Read: How Spain “Almost” Abandoned Philippines in 1765

‘The brave youth from Macabebe’

Not too distant from Manila was the pre-Hispanic Kapampangan settlement ruled by a young datu who would be known in history as Tarik Soliman (or Sulaiman). This early civilization is believed to have existed in Macabebe, possibly the present-day Sagrada, Masantol located at the mouth of the Pampanga River.

Also Read: 10 Reasons Why Life Was Better In Pre-Colonial Philippines

According to historian William Henry Scott, the royal families of Pampanga and Tondo had close ties. In fact, a man from Candaba named Dionisio Kapolong was Lakan Dula’s son. Hence, among the first ones to know about the recent events in Manila were most likely the Kapampangans.

This is exactly what happened when Tarik Soliman learned that Rajah Soliman and others agreed to kowtow to the colonizers. He couldn’t believe they had surrendered easily, so he did what a real warrior was supposed to do: fight.

Backed by 40 karakoas (ancient warship) and more than 2,000 highly-trained fighters from Macabebe, Hagonoy, and other nearby villages, Tarik Soliman sailed to Manila to accomplish his mission.

Fray Gaspar de San Agustin, the Spanish chronicler who authored Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas 1565-1615, was one of only a few sources of information about this obscure Kapampangan hero.

He referred to Tarik Soliman as “the brave youth from Macabebe” who led his men as they entered “the town of Tondo through an estuary called Bancusay without being seen by the Spaniards, where they stayed for a few days discussing with Lakan Dula the best way to start the battle.”

READ: 7 Myths About Spanish Colonial Period Filipinos Should All Stop Believing

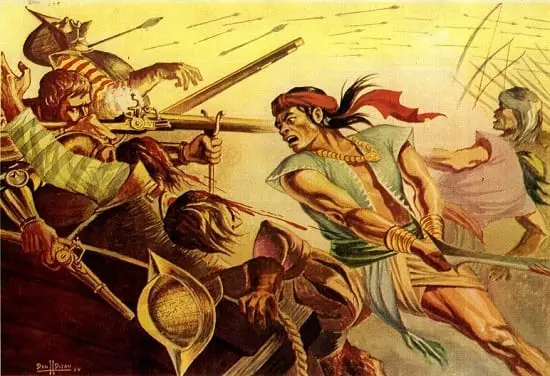

The Bancusay that Fray Gaspar was referring to is the Bangkusay’s creek, located off the north shore of Manila Bay. It was here where the bloody Battle of Bangkusay took place in 1571, a battle which would immortalize the heroism and extraordinary courage of a young warrior whose name continues to elude the Filipino consciousness.

A war (almost) nobody remembers.

Upon the Kapampangans’ arrival, Legazpi took a chance and sent two representatives to Lakan Dula’s camp. The goal was to convince Tarik Soliman of their ‘real’ intentions and talk him out of his plan to start an all-out war against the Spaniards.

But Legazpi’s wishes fell on deaf ears. The Spanish chronicler wrote Tarik Soliman’s response with colorful details:

“[Tarik Soliman] replied excitedly that neither he nor his followers wanted to see (Legazpi) nor have his friendship, nor that of the Castillians. Having said this, he stood up and with audacity and ferocity unsheathed his sword. Brandishing it, he said, ‘May the sun strike me in twain, and may I fall in disgrace before the women for them to hate me, if I ever became for a moment friend to the Castillians.’ (H)e left and without going down the stairs, to show his bravery, jumped out a window to the street then went directly to his caracoa. He told the Spaniards to inform their captain that he was waiting at the mouth of estuary, where he had entered, to fight. After saying this, he began sailing, amid hurrahs, to the place he mentioned.”

It dawned on Legazpi that the young Kapampangan warrior was really in the mood to fight. Therefore, he immediately ordered 80 Spaniards led by master-of-camp Martin de Goiti to face the furious Pampango warriors in Bangkusay.

On June 3, 1751, the two forces clashed, and the war ended with a lot of casualties. The defeat of the Kapampangans was almost expected, as they’re clearly outmatched by the Spaniards in terms of strategic weaponry. As said by William Henry Scott, the “Southeast Asian gunnery at the time was simply a matter of pointing guns at the enemy without taking aim.”

Among the hundreds of Kapampangans who perished that day, Tarik Soliman (who was referred to as “Bambalito” by the Spaniards) stood out in their memories. In a 1572 letter to the viceroy of New Spain, Legazpi himself described the slain warrior as “the only one who had obstinately rejected our peace overtures.”

After their defeat in Battle of Bangkusay, the Kapampangans slowly submitted themselves to the colonizers, culminating to the declaration of La Pampanga as Spain’s first province in Luzon in December 1571.

Also Read: Siege of Baler: A Story of Spanish Soldiers Who Just Wouldn’t Quit

The same people who once defied Spanish rule would later serve as mercenaries for the Spaniards. These Kapampangans “fought like mad dogs” against the Chinese pirate Limahong, the Moros, the Dutch, and the British led by Gen. William Draper.

Their fierceness extended even to the American period, during which the Macabebes played an often misunderstood role in the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo.

Macabebe scouts have long been accused of treachery by the Tagalogs, who have never heard of Tarik Soliman, nor of his heroic role in Battle of Bangkusay. History works in strange ways, and in the case of the Macabebe warriors, the tide had clearly turned.

What’s in a name?

It should be noted that “Tarik Soliman” is not the real documented name of our young Kapampangan hero. It first appeared as “Toric Soleiman” in Pedro Paterno’s Historia de Filipinas, and has since been widely used to prevent people from confusing him with Manila’s Rajah Soliman.

READ: Inside The “Royal” Life of Philippine History’s Ultimate “Balimbing”

According to Robby Tantingco, a cultural heritage advocate from the Juan D. Nepomuceno Center for Kapampangan Studies of Holy Angel University, the name “Bambalito” appeared thrice in a 16th-century document published by Lorenzo Perez in a 1933 journal.

It said: “Legazpi … sent two Spaniards to see Lacandola and in his house, they met the Macabebes, among whom was their chief named Bambalito, who swore to make war on the Spaniards and challenged them [to meet] in Navotas.”

As he explored its etymology, however, Tantingco became convinced that “Bambalito” may not even be the real name of the Kapampangan fighter. The Spanish suffix “ito,” which means “young,” was probably added by the Spaniards to emphasize his youth. Hence, by removing it, we could extract the name “Bambal” or “Bangbal.”

According to a Macau-based language expert Oscar Balajadia, ‘bangbal’ must have come from the root word ‘angba’ which means “crowd,” a nod to Bambalito’s reputation as a leader of a great crowd.

Whether he should be called Bangbal or Bambalito should not be the priority for now, as there is another more serious issue that threatens to relegate him to the dustbin of Philippine history.

Rewriting history.

For those who haven’t heard of him, it’s easy to confuse Tarik Soliman with Rajah Soliman, and vice versa. Although the original intention was to distinguish them from each other, the similarity in their names has made the whole thing messier than ever.

Also Read: 11 Things From Philippine History Everyone Pictures Incorrectly

The ripple effect is palpable. In some books, for example, the hero of the Battle of Bangkusay is Rajah Soliman, who reportedly died fighting the colonizers. Worse, some books even suggest that Rajah Soliman helped the Spaniards in fighting the Chinese pirate Limahong–years after he supposedly died in Battle of Bangkusay.

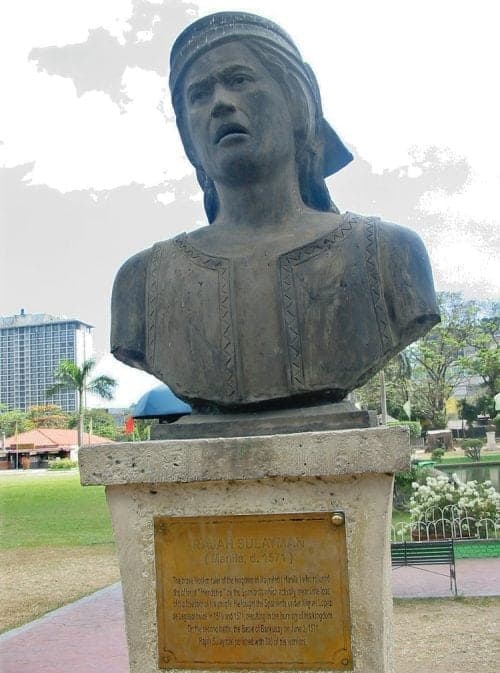

The same is true with famous works of arts and monuments–including the one in Luneta–which incorrectly name Rajah Soliman, instead of Bambalito, as the slain hero of Bangkusay.

Bambalito may not be the first documented hero who fought against the invaders (Lapu-Lapu holds that distinction), but he was the first martyr killed while fighting for our freedom. A reason good enough to rewrite the history being taught in our schools.

Also Read: 5 Great Philippine Heroes Nobody Remembers

So each time you read about Philippine heroes like Rizal, Bonifacio, and Lapu-Lapu, may you remember that before the Spaniards completely deprived us of our freedom, a young man chose to stand up and fight for what he believed is right.

An extraordinary warrior indeed, and a brave hero every millennial should look up to.

References

99 Kapampangans Who Mattered in History, and Why. Singsing Magazine, (Vol.2, No. 3).

Chua, M. (2015). Kasaysayan: Si Bambalito, ang unang martir para sa ating kalayaan. GMA News Online. Retrieved 30 May 2016, from http://goo.gl/GrQaVG

Halili, M. (2004). Philippine History (p. 80). Rex Bookstore, Inc.

Mallari, P. (2014). Macabebes as warriors and mercenaries. The Manila Times. Retrieved 30 May 2016, from http://goo.gl/Uz7P9x

Orejas, T. (2013). Homage to local hero endures in Pampanga town. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 30 May 2016, from http://goo.gl/2djPa3

Scott, W. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press.

Tantingco, R. (2014). First Filipino to die defending his country was a Kapampangan. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/gq9up8

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net