9 Interesting Jobs From Old Philippines That No Longer Exist

As technology evolves, so do the way people earn money. For this reason, some of the things that kept our great-great-grandparents busy have slowly disappeared or transformed into their modern-day counterparts. Let’s pay tribute to these fascinating old-timey jobs and the equally fascinating stories that led to their demise.

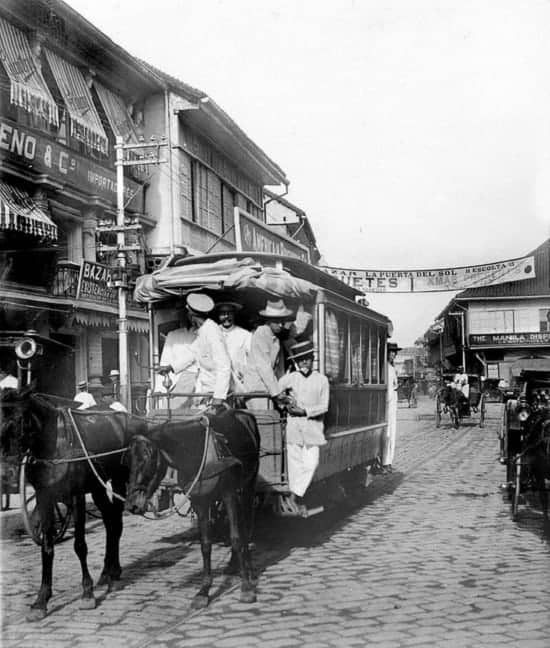

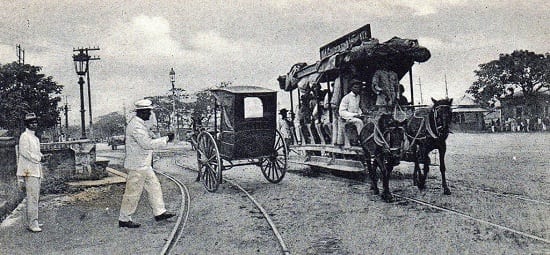

1. Horse Tram Driver

Long before the jeepneys, buses, and Manila’s Light Rail Transit (LRT) joined forces to provide us with a horrendous mass transportation system, our ancestors relied on the good ol’ tranvia.

It was first introduced to Manila when the Compañía de los Tranvías de Filipinas, owned by Jacobo Zóbel Zangróniz and his partners, was given the right to operate the first tramcar service in the city capital. These horse-pulled tranvias could accommodate 12 to 14 people, all evenly distributed on both sides to avoid the streetcar from toppling over.

Also Read: 22 Things We No Longer See in Manila

Unlike the tranvias in European countries, those we had here were “very casual in operation,” as a visitor once remarked. And by “casual,” he was most likely referring to instances when passengers had to get off and help push the vehicle towards ramps. The quality of the service depended on the health of the horse and the professionalism of the horse tram driver.

Made of steel and wood, the horse trams operated in five city routes, with Plaza San Gabriel (present-day Plaza Cervantes) as its central station. Drivers were hired by the company to operate two types of horse-drawn tranvia: the open tramcars equipped with curtains that could be adjusted to alleviate summer heat and the closed tramcars designed to shield the passengers during the rainy season.

READ: 29 Things You’ll Never See in Manila Again

During the American Occupation, the Compañía was absorbed by the Manila Electric Railway and Light Company (MERALCO) which got the franchise for the first electric streetcar system in the country. After reaching its peak in the 1920s, Manila’s streetcars were wiped out during WWII. Jeepneys and buses soon proliferated the city, serving as Manila’s main modes of transportation until the construction of the first LRT system in the 1980s.

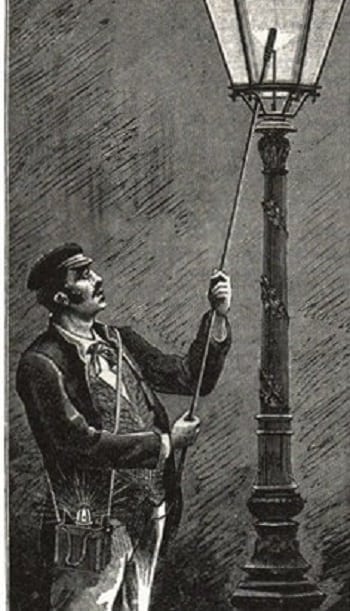

2. Farolero (Lamp-lighter)

In 19th century Philippines, streets in Manila—like those in Sta. Cruz district– were illuminated by lamp posts that were lit using kerosene. Every twilight, faroleros or lamplighters employed by the city government would go about the streets with their collapsible “bangko-lobo” (“lobo,” a corruption of “globo,” spherical glass dome lamps) to light the wicks of the lamp.

Also Read: 17 Most Unusual Street Names in Manila (And Their Origins)

Faroleros were also paid to maintain the street lights. The job became obsolete with the arrival of electricity in the Philippines. In 1890, Thomas-Houston Electric Company installed the first electric street lights along Luneta.

3. Umalohokan (Town crier)

To establish order in the community, the pre-colonial chieftain of a barangay was compelled to enact laws. With the approval of the village elders, these new laws would then be publicly announced by an umalohokan, the ancient counterpart of today’s broadcaster.

Also Read: 10 Reasons Why Life Was Better In Pre-Colonial Philippines

Also known as the public announcer or the “town crier,” this person would go around the barangay to spread the news about the laws. Historian Teodoro Agoncillo provides more details: “With a bell in one hand, the umalohokan called the attention of the subjects by ringing the bell furiously. The people gathered around him and heard from him the provisions of the new law. Anybody violating the law was promptly arrested and brought before the chieftain to be judged according to the merits of the case.”

4. Grabador ng Plato’t Baso (Tableware engraver)

There used to be itinerant engravers with their small jeweler’s chisels and hammers who offered engraving and etching services to identify family tableware. Precious porcelain plates, enamelware, cups, crystals, saucers, spoon, forks and silver cutlery were etched or engraved with the monogram or initials of the owner, by pounding “dots” to form individual letters.

A pair of steady and controlled hands is needed to perform the delicate process, lest damage is done on valuable china. Today, engraving is done by machine, sometimes even done free by commercial shops, rendering manual engraving service obsolete.

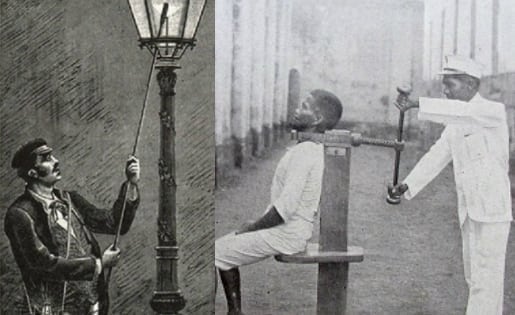

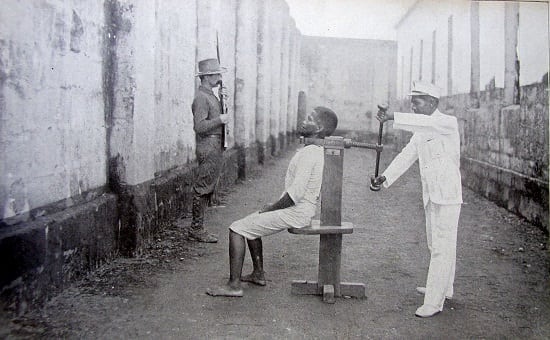

5. Garrote Executioner

The Spanish colonizers brought to the country several methods of capital punishment. Criminals and convicted enemies of the government suffered death through hanging, shooting, burning, and decapitation, just to name a few.

Also among these methods was the garrote, which became so notorious not only for killing the martyr priests GOMBURZA but also because people think it involved a slow, painful death by strangulation.

Also Read: 13 Most Famous Last Words Ever Uttered in Philippine History

However, nothing could be further from the truth, especially if you’ll read the eyewitness account by Joseph Earle Stevens. In 1898, his memoir entitled “Yesterdays in the Philippines” was published and inside it is a rare personal account of a garrote execution he witnessed in Manila on July 4, 1895.

Driven by scientific curiosity, Stevens joined many others in viewing the garrote execution of two native Filipino boys, aged 20 and 22, who were sentenced to death after robbing and butchering their Spanish master. The execution was supposed to be done behind Luneta, but public protest prompted then Governor General Blanco to move the place of execution somewhere near the Manila slaughterhouse.

Also Read: 10 Surprising Facts About Death Penalty In The Philippines

Describing the execution method, he said “death comes instantaneously from the snapping of spinal cord.” He also gives readers a glimpse of the berdugo or the garrote executioners, their background and how much they earned from breaking someone’s neck:

“The executioners in Manila have always been themselves criminals, and in breaking the spinal cords of their fellow criminals, they certainly pay a price for keeping their own vertebrae intact. Like most men in their profession, however, they are well paid, and this operator got sixteen dollars besides his regular monthly salary of twenty, for each man on whom he turned the screw.”

When the Americans took over the Philippines at the dawn of the 20th century, they chose to keep garrote as a method of execution. It was abolished in 1902.

6. Lechero (Milkmaid or Milkmen)

Editor’s note: The practice of peddling milk still persists in a few rural markets, but nowadays, hard-to-find carabao’s milk is packaged in ketchup bottles.

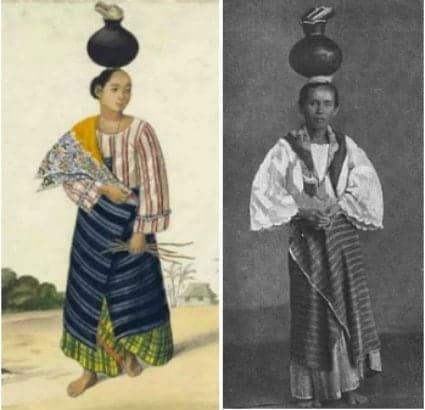

In the days of yore, ambulant milk vendors or lecheros/lecheras plied the town streets with their fresh gatas kalabaw (carabao’s milk) dispensed from metal pitchers, earthenware crocks or from dried gourds.

Also Read: 0 Amazing Things We No Longer See In Pasig River

In the book The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes 1521-1935, food historian Felice Prudente Sta. Maria shares an interesting description of a Filipina milkmaid originally published in Ilustración Filipina, a Spanish language magazine which ran from 1859 to 1860:

A milkmaid “accepts monthly payments, and only in very special cases will ask for advanced payments.” She usually carries an earthen jar on her head because “she is not used to carrying an umbrella, nor would she use it without running the risk of ruining her merchandise.” The said jar was half-covered so as to prevent the milk from getting sour. A chupa was also placed at the jar’s mouth which the milkmaid used for measuring.

A Filipina milkmaid at that time was known for her professionalism, punctuality, and speed. It is said that milkmaids’ “movements have a certain regularity resembling the handling of arms by the militia.”

By 1878, Filipinos could contract La Perla Oceano, located at 23 Crespo Street in Quiapo, to deliver daily supply of fresh carabao milk to their homes. Others still preferred to get their milk from independent lecheros/lecheras who would station themselves strategically near the public market while others would line the main road. By mid-morning, their milk-selling duties would be over.

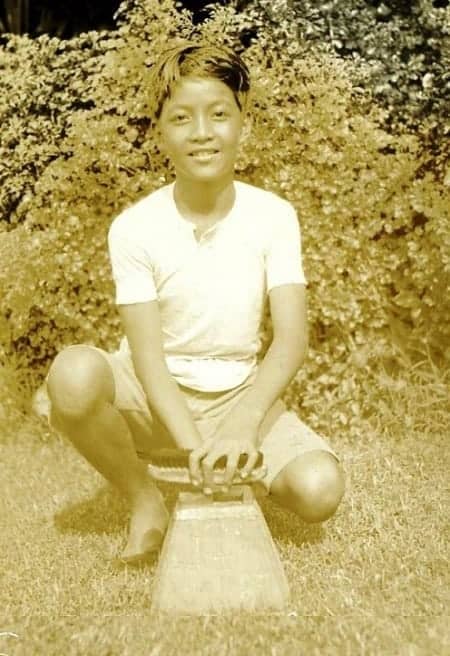

7. Limpia Botas (Shoeshine boys)

Editor’s note: Young and older adults still offer shoe-shining service in some parts of the country, particularly in Baguio City. However, “shoeshine boys” (emphasis on the age) are basically non-existent.

Back in the 1930s through the 1960s, Filipino street boys could earn an honest living by shining shoes, thanks to the invention of the shoe polish in the early 20th century.

Limpia botas, or bootblacks, with their homemade shoe cleaning kit that included brushes, “biton” (shoe polish wax) and dyes, and pieces of rags for buffing leather shoes. The handle of the kit doubles as a shoe rest, so the limpia botas could work on the shoes from all angles.

Also Read: The Filipino Boy Who Became A WWII Hero At 11 Years Old

As late as the 1990s, shoeshine boys could be seen in the city’s commercial areas like Ermita, where tourists and office workers are concentrated. As shoe shining consumed more time, boys gave it up for quicker money-making jobs—watch-your-car, parking aide, and vending among others.

Besides, customers began favoring shoe service shops that offered all-in-one shoe shining, and general repair.

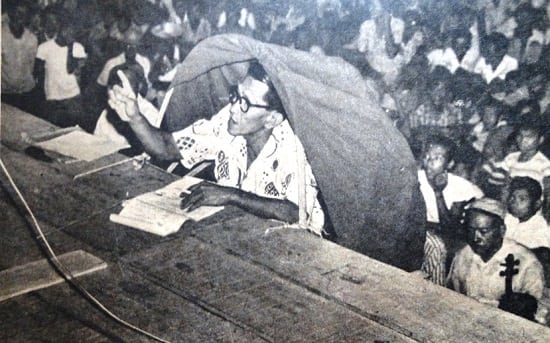

8. Apuntador ng sarswela (Zarzuela prompter)

The zarzuela (sarsuela) is a theatrical play from one to five acts that features singing and dancing. It was adapted from Spain and by the 1900s, sarsuelas were being staged in Manila and in provinces like Ilocos, Pampanga, Cebu, and Iloilo.

Mounting such elaborate musical operettas involved people working behind the scenes—from the maestro del coro (choirmaster), telon (curtain) raiser to the prompter, or apuntador—in case the actor forgets the lyrics of the song or misses a cue to exit.

Did you know? Andres Bonifacio was a theater actor

With a script in hand, the apuntador coaches in front of a covered portion of the stage, using a “concha” or a conch shell to direct his voice discreetly to feed an actor his lines. Zarzuelas are rarely staged these days, and prompters have become optional, with such modern-day stage aids like teleprompters and earphones.

9. Lagarista (Film Reel Courier)

Before digital films, movies were shot on rolls of film acetate, from which a number of prints were made. Since these were limited in number, a movie house courier had to pick up and deliver film prints rolled in circular cans to other movie houses in the city according to each cinema’s showing schedule.

Also Read: 22 Things You Didn’t Know About ‘Heneral Luna’

Called “lagaristas” (from “lagare,” a carpenter saw, slang for someone who goes back and forth, from one job to another), they usually ride on bikes so they can quickly navigate the city roads to ensure timely delivery of the film rolls, in all kinds of weather.

Technology has made it possible to shoot films on a digital format, that could be stored in mediums such as a memory card or CDs. These can be reproduced cheaply and distributed easily, for showing in cinemas.

BONUS Trivia: Disappearing Pinoy Jobs

Gareta/Kalesa Wheelwrights (Wooden wheel makers).

Wheelwrights—maker of wooden wheels—were essential in every rural town that depended on carts with wooden wheels to transport their produce. They not only made solid hardwood wheels ringed with iron but also built wheels for kalesas, carriages and carrozas.

Also Read: 9 Philippine Icons And Traditions That May Disappear Soon

The advent of rubber tires, first made in the mid-1800s caused the disappearance of wooden wheels as well as the wheelwright trade. They rolled quieter, moved smoother as they had more traction, and were longer-lasting. Today, only a handful of wheelwrights are in operations to service kalesas that are still in existence in some parts of the country.

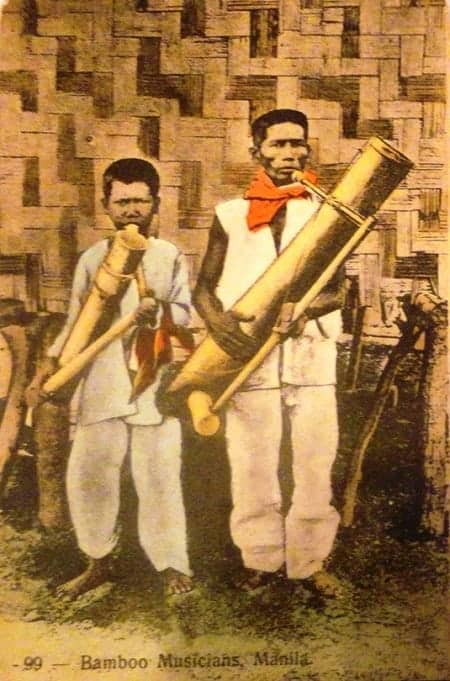

Musikong Bumbong (Bamboo musicians)

Early Filipino musicians discovered that the hollow bamboo could be made into a musical instrument— a flute, an angklung, a tuba, a clarinet, or even a xylophone.

READ: When Filipino Underdogs Made History At A US President’s Inauguration

In the 19th century, small band musicians would often make the rounds of town fiestas to make a few centavos by playing these improvised bamboo instruments. Soon, a whole ensemble of bamboo musicians was organized into bands like the legendary “Banda de Boca” of Malabon, that began in the 1890s and which comprised of katipunero-musicians.

Although bamboo was readily available even to poor musicians, it was subject to cracking and insect infestation. Metal instruments found favor over these hand-made bumbong music makers, leading to the exit of these bamboo-carrying troubadors.

About the Author: Alex R. Castro is a retired advertising executive and is now a consultant and museum curator of the Center for Kapampangan Studies of Holy Angel University, Angeles City. He is the author of 2 local history books: “Scenes from a Bordertown & Other Views” and “Aro, Katimyas Da! A Memory Album of Titled Kapampangan Beauties 1908-2012”, a National Book Award finalist. He is a 2014 Most Outstanding Kapampangan Awardee in the field of Arts. For comments on this article, contact him at [email protected]

References

Agoncillo, T. (1990). History of the Filipino People (8th ed., p. 44). Quezon City: C & E Publishing, Inc.

Alcazaren, P. (2015). The tranvias of Manila. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 9 September 2016, from http://goo.gl/CVzKNF

Ayala and the Manila tranvia. (2012). Ayala Now, 19. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/rULPno

Fernando, G. & Ricio, N. (1978). Turn of the Century (p. 108). GFC Books.

Sison, N. (2015). LRT expansions remind of tranvia days. VERA Files. Retrieved 9 September 2016, from http://goo.gl/uLsjl8

Sta. Maria, F. (1983). Household antiques & heirlooms (p. 80). GCF Books.

Sta. Maria, F. (2006). The Governor General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes 1521-1935. Mandaluyong City: Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Stevens, J. (1898). Yesterdays in the Philippines. Scribner.

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net