The Bizarre Life And Ugly Death of the Man Who Challenged Marcos

Undoubtedly, election season in the Philippines always brings with it a circus-like atmosphere complete with the strange and the bizarre. And contrary to popular belief, the Filipinos of yesteryear also had to contend with their own fair share of strange candidates, ones whose platform for governance and behavior would leave you either amused or scratching your heads.

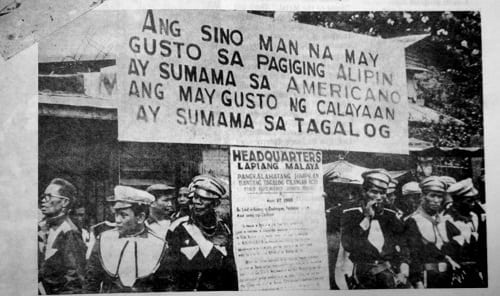

Valentin Delos Santos was one such man. The founder of the religious-political party slash millenarian sect Lapiang Malaya (Freedom Party) which had around 40,000 members (mostly farmers and poor folk from South Luzon), Delos Santos was an enigmatic and colorful character.

Regarded by his followers as a holy man who could converse with Bathala and the spirits of past Filipino heroes, the Bicolano Delos Santos was a perennial presidential candidate, having ran first against Carlos Garcia in 1957, Diosdado Macapagal in 1961 and then against Ferdinand Marcos in 1965 with the promise of achieving “true justice, true equality, and true freedom for the country.”

Also Read: 13 Intriguing Facts You Might Not Know About Ferdinand Marcos

However, his endeavor was met both with amusement and disdain by the public and his political opponents who believed him to be a crazy old coot.

Two years after losing to Marcos, Delos Santos—then already in his 80s—led around 400 of his followers who were dressed in strange blue uniforms with capes on a march from Taft Avenue in Pasay to Malacañang Palace to demand the president’s resignation. Delos Santos cited poverty, landlessness, and the country’s exploitation by Western powers as his reasons why Marcos should resign.

Facing off against the Lapiang Malaya members who were wielding only bolos and amulets were heavily-armed troops of the Philippine Constabulary (PC) who cordoned off the area leading to the Palace. Then just after midnight of May 21, 1967, all hell broke loose as the soldiers opened fire at the charging rallyists who initially ignored their warning shots because they thought their amulets and anting-anting would protect them.

When the chaos was over, 33 members of Lapiang Malaya and one soldier lay dead on the street. Dozens more—members, soldiers, and civilians—also suffered gunshot or hack wounds.

READ: A Tale Of Two Presidents: Did Nixon Approve Marcos’ Martial Law?

Following the short-lived uprising, Delos Santos and 11 of his chief aides were arrested and charged with sedition. Rather than facing trial, however, they were instead brought to the National Center for Mental Health where they were evaluated and declared to be insane.

In August of the same year, Delos Santos met his end inside the center at the hands of his schizophrenic cellmate. Mauled in his sleep, he slipped into a coma and was never revived. The doctor of the facility later officially attributed his death to pneumonia.

While the movement and the uprising faded from public memory soon after Delos Santos’ demise, the group’s off-shoot Vucal ng Pananampalataya can still be seen to this day living in relative peace in the mountains of Nueva Vizcaya.

References

Celoza, A. (1997). Ferdinand Marcos and the Philippines: The Political Economy of Authoritarianism(p. 28). Greenwood Publishing Group.

Cua Lim, B. (2009). Translating Time: Cinema, the Fantastic, and Temporal Critique (p. 254). Duke University Press.

Taguinod, F. (2008). Lapiang Malaya branch holds ‘lechon festival’. GMA News Online. Retrieved 14 October 2015, from http://goo.gl/V8zzgb

Watawat.net,. Lapiang Malaya. Retrieved 14 October 2015, from http://goo.gl/CayYO8

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net